Imagined Images

A missing family photo album recreated with the use of generative AI

My great-grandparents, my grandparents, and my parents changed the place of residency many times before I was born. Sometimes forcibly, sometimes at will. The photographs that documented the events of their lives were lost along the way. I don’t really know much about them, except for some stories I’ve been told about where they lived and what their profession was. I took all these stories and used them as prompts in an image-generating AI to rewrite my own history. Unexpectedly, that process was not only emotional but also informative. The AI seemed to know more than I did about a specific place and time, adding details to images that I wasn’t aware of.

Moments that happened, moments that were unphotographed, moments I imagined, moments I was told about, moments I have hoped to happen, moments that never happened.

How can one rewrite his own history?

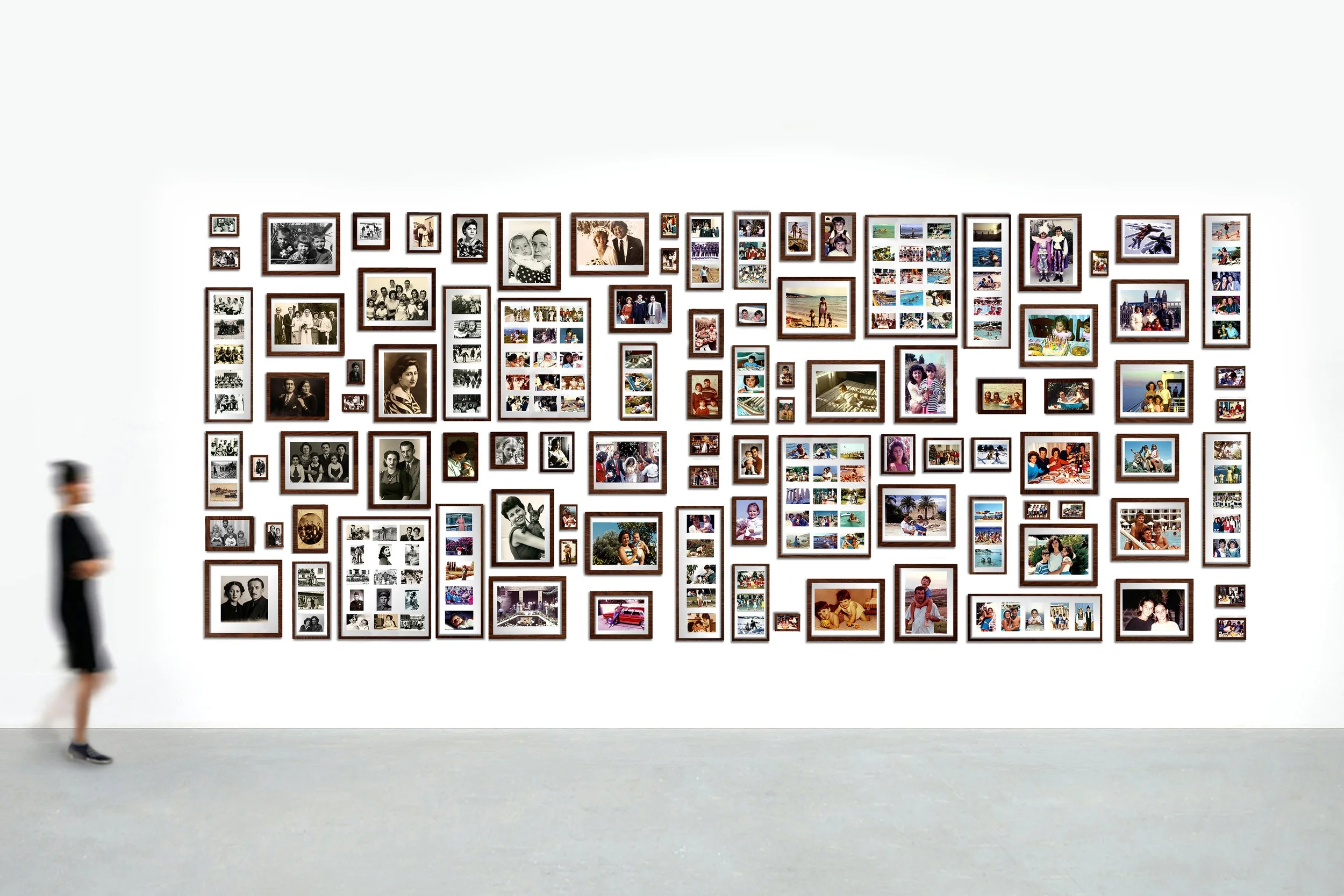

Installation proposal

Imagined Images

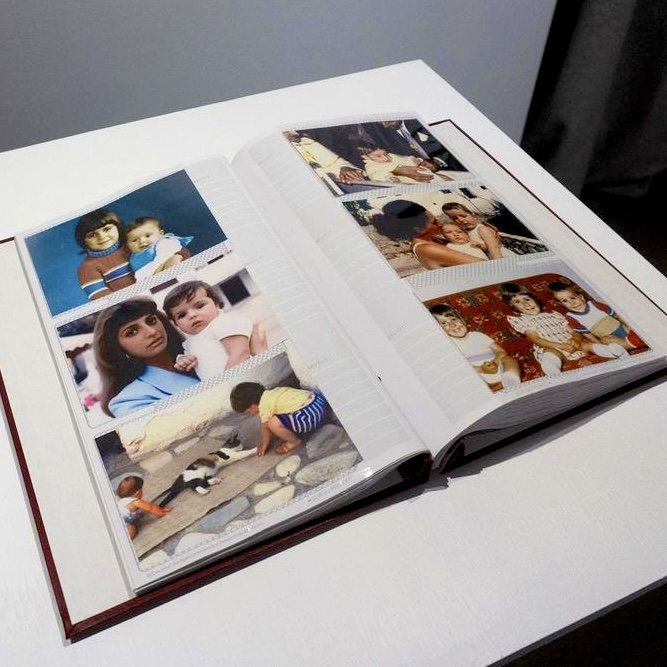

What is the use of a photograph? If nothing else, it’s a reference point to a specific moment in time, the moment of its creation, the moment it depicts. Especially family photographs are a tie to our personal history, an archive of who we are and where we came from. They are “memory deposits” from where we keep sourcing the certainty of our life events even if our memories of them are lost. In this project, personal memories are absorbed by A.I. and meshed with thousands of others to become a new breed of images, images resembling uncannily those of our childhood photo albums. But what is the use of this new kind of image since they lose their fundamental tie to reality? What is the memory they hold? To whom are they precious, heirlooms that must be preserved?

Imagined Images is a series of AI-generated images that I created to reconstruct my family photo album which is missing. Due to the numerous relocations of my ancestors, sometimes forcibly and others at will, resulting the photographs that documented the events of their lives getting lost along the way. My great-grandparents, my grandparents, and my parents changed the place of residency many times before I was born. I grew up without a family photo album; the past had no image for me, which left me feeling unrooted in a way. I am a daughter of immigrants who grew up in Greece; my father grew up as an immigrant in Uzbekistan; my grandfather had to flee from Greece during the civil war; my great-grandmother had to flee Istanbul as a Greek minority in Turkey, and so on it goes for the past generations of my family that I am aware of. Each one of us, dating back at least a century, had to move from one place to another during their lifetime at least once, and start from scratch, to build a life that soon had to be abandoned again, in order to survive. I’ve never seen the house I was born in. I’ve never seen the park I did my first steps. I never met my grandmother.

Using my family’s and relatives’ narratives as prompts, I created images that don’t truly belong to me, but could represent anyone’s story. While actual photos are used as a means to preserve memories, these images are the exact opposite - they are images created by memories. Family albums typically highlight happy moments, celebrations and milestones, while hardships, difficulties, struggles and loss are left unphotographed, as if to be forgotten. Trying to reconcile with my family history, one of displacement, loss and deprivation, I visualized with the use of DALL·E-2 moments that happened, unphotographed moments, moments I imagined, moments I was told about, moments I have hoped to happen, moments that never happened. We used to say that “an image is worth a thousand words” but today a word can produce infinite image variations, reversing that relationship. How will these AI-generated visuals change our image economy?

Unexpectedly, the process was not only emotional but also informative and even therapeutic. The AI seemed to know more than I did about a specific place and time, adding details to images that I wasn’t aware of and that my parents were able to confirm their truthfulness. That unexpected aspect of AI-generated images led me to realize that there is a kind of truth in those images (when the prompt allows for that) that I call a “statistical truth.” AI-images are derivatives of photographs, an amalgam, an average of billions of other images, yet may that bring them closer to a more universal kind of truth of phenomena? May they be a mirror through which we may look back on our society?

The project reflects my personal journey of recreating a fragmented family archive through the use of Artificial Intelligence, and in doing so, it resonates with broader questions around intergenerational genealogies, memory archives, and the practices of storytelling. The resulting images stand in the middle ground of private and public, informed by the vast amount of AI’s training data, they are automated-produced by a machine and not a human photographer- and they are fundamentally different from photos, in the sense that these images are created by memories. The fact that the faces in the images are unrecognizable due to AI’s early version’s inability for fully photorealistic results seems to intensify our ability to relate to those uncanny images. They are not mine, yours, or anyone’s, but they belong to all of us. The aura is there. The surface of the image is just a stimulus; it’s a certain point that functions as an anchor to a place and a time; it’s a directory, a path, a link to memories and feelings.

In a time when war conflicts, refugee flows and right-wing ideology are on the rise, I couldn’t help but wonder what it would mean for one to be able to rewrite his own life story through images that might soon be indistinguishable from real photos.

What is the use of a photograph? If nothing else, it’s a reference point to a specific moment in time, the moment of its creation and the moment it depicts. It is also about the subject it depicts, the occasion, the person, the act, or the scene it shows.

Especially family photographs are a tie to our personal history, an archive of whom we are and where we came from. They are “memory deposits” from where we keep sourcing the certainty of our life events even if our own memories of them are lost.

The photographer, in this case, is usually someone we know, our dad or mum, aunts and uncles, family friends and relatives, someone we would invite to be next to us in the most important events of our lives, someone we would open our house to, someone we would trust with a funny face, an embarrassing outfit, a personal moment. A human.

Though, it’s a long time now since humans are not the only creators of images anymore. Automated cameras, various scanners, Artificial Intelligence systems, and GANs are all able to produce images.

In this new project personal memories are absorbed by A.I. and meshed with thousands of others to become a new breed of images, images resembling in an uncanny way those of our childhood photo albums although everything is translated to a mere set of forms, points, colors, and tonalities.

But what is the use of this new kind of image since it loses its fundamental tie to reality? What is the memory they hold? To whom are they precious, heirlooms that must be preserved?

Plato would probably classify them as third-grade mimesis and thus reject them as a means of even further diversion from the truth of Ideas, but is there any chance that Aristotle would appreciate them for the insight they may give to the learning process and the potential of catharsis that they may offer?

If the danger of photography was our belief in its inherent truthfulness (a belief that has been challenged ever since) may there be the same danger in qualifying AI-generated images fake? Fake in comparison to what? Untruthful to what kind of truth? AI-generated images are derivatives of photographs, an amalgam, an average, of billions of other images, yet may that bring them closer to a more universal kind of truth of phenomena?

The etymology of the word image has its roots in the Latin word imitari, meaning "to copy or imitate"; and the words imagine, imagination, and imaginary derive also from the same root. Although today we use the word imagination usually in a context that predisposes us to something new, that newness seems to derive from the ability to imitate and copy the already existing. In that light, AI-generated images are ontologically equal images to any other image preceding them.

AI-generated images have a peculiar relationship with time. Unlike photography, they are not tied to a specific point in time through the scene they depict, rather they can imitate this link. Trained on billions of images, AI has assorted the style and color grading of the medium humans have used to create images in the past. Especially when a photographic result is requested specifying the time and the place that an image was created, for example in the 60s, AI adjusts the colors and the overall feeling of the generated image accordingly. But how will we be able to date AI images when looking back in time? Deformations, distortions, ambiguity in the form, and the “in-house” style are the giveaways.

Moreover, AI-generated images have no actual form of their own. They tend to mimic the style and aesthetic of other mediums, be it painting, photography, or digital art.